Whether we call it nondual awareness, unity, oceanic feeling, or universal love, we have inadvertently placed such an experience out of reach and available only to mystics, saints, and special others. However, as I have written previously, we are born with this unique sense of being only to apparently forget it as our ego and individuality develop. The dark curtain covering our oceanic feeling, or okeoagnosia (from the Gr. okeanos or ocean and agnosia), is, however, overcome through meditation, prayer, inquiry, falling in love, paying attention, or with drugs. It is remarkably recoverable.

The argument I want to make today is that the news is even better than that. If we think of recovery from okeagnosia as a path, then such a path starts from the awareness that we already have a unity experience. We have it moment-by-moment since it is intrinsic to our human nature. What is needed is to “increase” that sense of being. One can do this by focusing on particular aspects of it, such as enhancing our emotional presence (heart) and unifying it with our intellectual presence (mind) (An Enhanced Sensory Experience). In the end, we gauge progress by the regained sense of joy, love, wonder and curiosity.

The following describes a path of recognition, realization, and appreciation that may be cultivated:

- Attend to how you see, hear, feel, and think of the external world. Whether you see it as full of independent things with which you interact in a distant, objective, cold, or analytic way or as close, intimate, and loving entities.

- Realize that your experience of the world (objects, feelings) is the result of your brain’s activity. You are a co-creator of that world and partly responsible for what you experience.

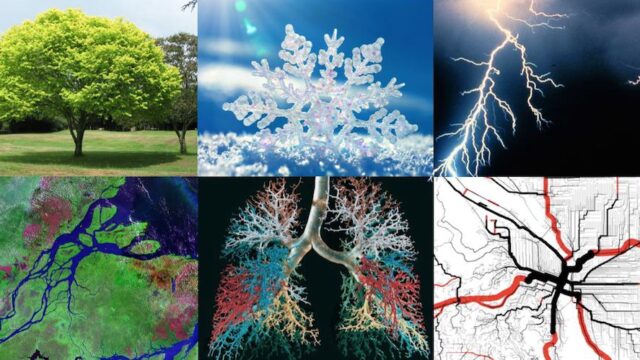

- Realize that you see the world as individual parts but also holistically.

- Recognize your care for this external, holistic world because what happens out there affects you inside in small and big ways, especially what other people do. Begin to see this common ground.

- Recognize that caring can extend not only to others like yourself, but to animals, plants and everything in between. See the common ground in all.

- Realize that the feelings of caring for all of life takes on a sense of intimacy and closeness. The coldness gives way to love and compassion.

- Recognize that unity reflects an intrinsic sense you have but forgotten.

- Recognize that this experience of unity is possible in others as in yourself (Trusting Stillness).

- Recognize that it reflects a non-separation, compassion, and love knowingness (Unencumbered Original Mind).

- Realize that you experience unity when you participate in some activity in which you lose track of things, of time, of yourself, etc.

- Appreciate that you experience unity when in love or during focused attention where your ego disappears in the presence of someone special (lover, wife, husband, children) or something that interests you to the exclusion of everything else.

- Appreciate that as you move down this path of recognition and realization, life becomes more joyous, your curiosity increases, as does love and compassion toward others.

- Appreciate that as you move down this path, you begin to feel a greater connection, less distance and more intimacy between you and the world.

- Appreciate that outside and inside are the same. What appears to be outside is also inside. Figure and ground are just different aspects of the same thing. They define each other but are the same. No greater intimacy than this.

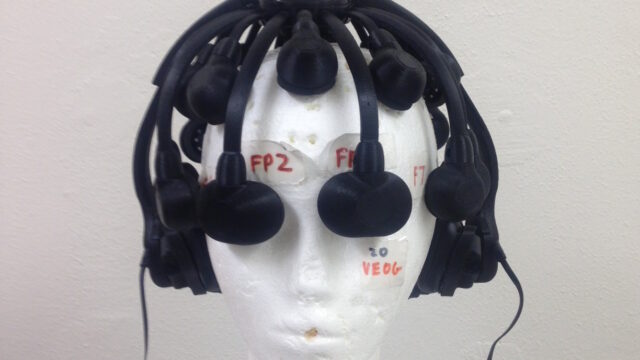

In the rest of the blog, I only want to address the first and most important assumption: That we already have a unity experience. Many will undoubtedly balk and argue that it is not so and are not convinced. This is because we all have different notions of what unity means. We may not agree but let’s start by trying to define a common starting point. At the most basic level, a unity experience means that our perception of the world isn’t a jumble mess of sights, sounds, and emotions, scrambled in such a way that what we experience does not make sense.

In his 1890 volume Principles of Psychology, William James, the founder of American psychology characterized a baby’s experience as such: “The baby, assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion.” Yet, developmental psychologists now know that James was decidedly wrong. Even at an early age, as we close and open our eyes, what we experience is not a scrambled set of sensations but a unified world that we understand and that makes sense.

Such an integrated, unified world has orderly physical laws that make prediction of events possible compared to a chaotic or random system. Because we live and are part of such a unified, orderly world, humans have evolved unique prediction algorithms to anticipate outcomes, understand the meaning of actions of others, etc. (Reducing Uncertainty in a Chaotic World and Our Predictive Brain).

Unified implies an experience of closeness, intimacy, and love. Each one of us comes into environments varying in love and acceptance. This can either extend our intrinsic unity experience or cause the dark curtain of okeagnosia to descend quickly. How thick that curtain is distorts and destroys our sense of unity. And it affects how we feel toward others and our environment. We become distant, cold, unemotional, fearful.

Now that you know, are you ready to step into the path of regaining the greatest gift you were born with, the jewel at the center of your being? Start by asking yourself, which sense did I display as a baby? What sense do I display now? How do I get from here to there?