We all have ideas about what meditation is. It means many things to different people—a tool, a religious path, a lifestyle. At its root, there is a sense of gathering, of bringing together and focusing the resources of attention on the present moment. Meditation practice brings this awareness to a narrow or broad focus, along with a certain gentleness and care, to reduce our reactivity to life events. As we become proficient in the skill, the spotlight of attention falls on either simple or complex targets. A major focus is our own mind and its helter-skelter motifs, replete with uncertainty, randomness, and emotional pain. At some point, we attend to that which holds all objects of attention—awareness itself.

We practice these skills to relax, for health reasons, or to explore spiritual matters. How we meditate varies, either sitting, lying down, walking, chanting, dancing, or carrying on with our life. Each mode and approach offer valuable experiences and important insights. Mindfulness, qi jong, yoga, mantras, TM, prayer, progressive relaxation, Dzogchen, Zen, Sufi dancing are all part of what one imagines when the word is mentioned. Because there are so many styles and variations, the practice of meditation, and what might be its outcome, seems complex, confusing, and unnecessarily complicated.

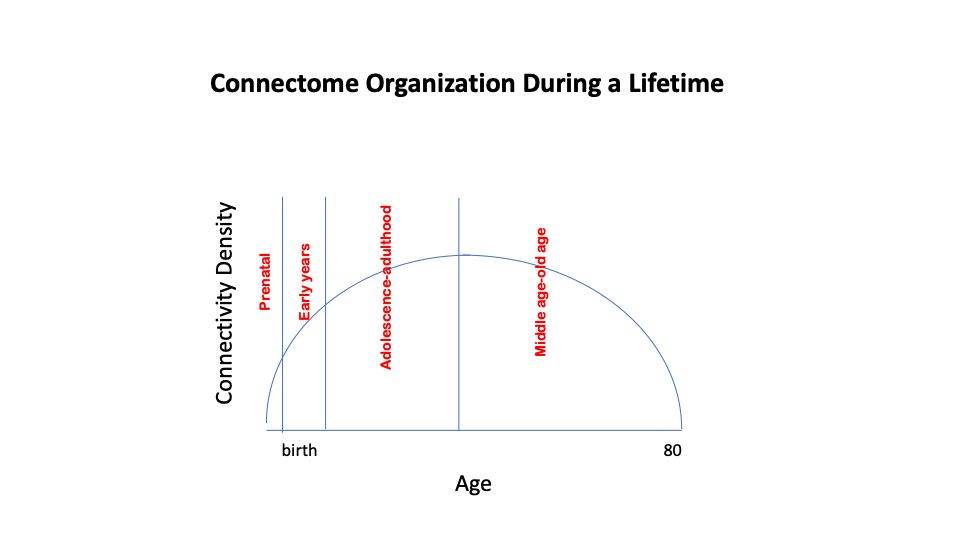

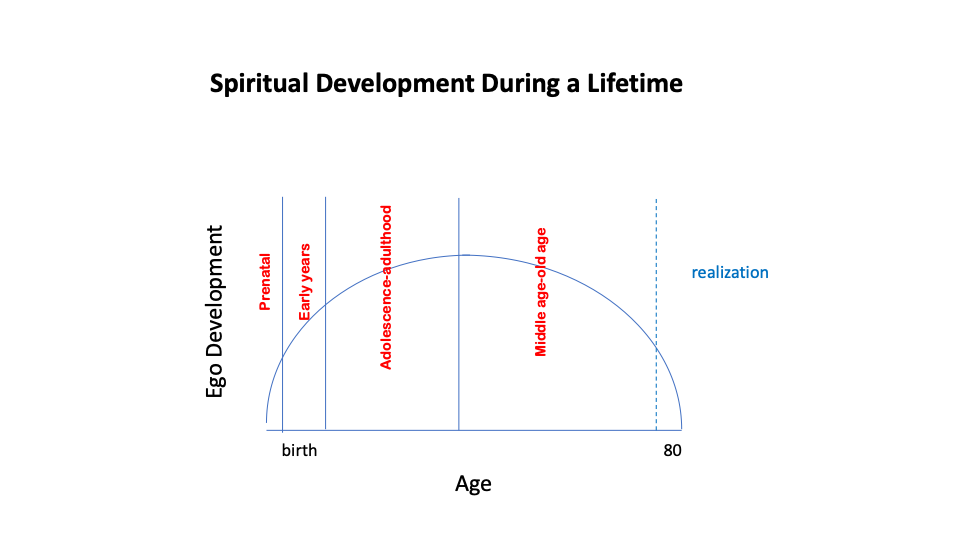

As a psychological and health improvement practice, the consistent routine of meditation reduces stress, anxiety, memory loss, negative emotions, and pain, while improving heart rate, concentration, sleep, emotional health, patience, tolerance, imagination and creativity. These positive outcomes fuel the growing interest. As it assumes a spiritual orientation and lifestyle, meditation becomes especially intricate. An aspiration in this approach is to reconcile with an initial unity we experienced as children. Limitless paths exist to such unity, involving concepts of God, Buddha-nature, the Source, enlightenment, kensho, satori, wakefulness, realization, etc. and innumerable methods and techniques to help us get there. Just like the act of driving remains the same regardless of the vehicle you use, despite the hundreds of variations, styles, and gadgets associated with driving, meditation from a spiritual perspective remains straightforward. At its most basic, it concerns mental and spiritual health, and the rediscovery of the real you.

I would argue there are only three absolutely necessary actions needed to practice meditation, everything else is optional.

- Be present-moment centered and focused on: “Who is present?”

- Stop identifying with mind and body

- Trust and surrender to the non-conceptual awareness that arises.

Regardless of your particular method and technique, consistently practicing meditation as an act of love towards yourself and others, whether as a secular or spiritual intention, will help you develop and fine-tune the following unique traits:

Stillness: More than the absence of movement, stillness is an attitude that “life is perfect as it is” or more prosaically that “life is what it is.” It is the reality which is in front of us — a single outcome out of a set of infinite possibilities given the history and circumstances of each moment — and which we accept and have no need to change.

No-mind: This comes from a Buddhist martial arts term, Mushin, that translates literally as no-mind. It refers to a mind that is not fixed or occupied by thought or emotion and open to everything. An unencumbered mind that lacks self-centeredness and flows unimpeded from moment to moment. Also associated with the term “beginner’s mind” and “compassionate mind.”

Flow: Overlaps with the idea of “no-mind.” It is the sense of being completely immersed and absorbed in an activity or task, in which we lose a sense of space and time. The psychologist Mihály Csikszentmihályi described it as when “The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.”

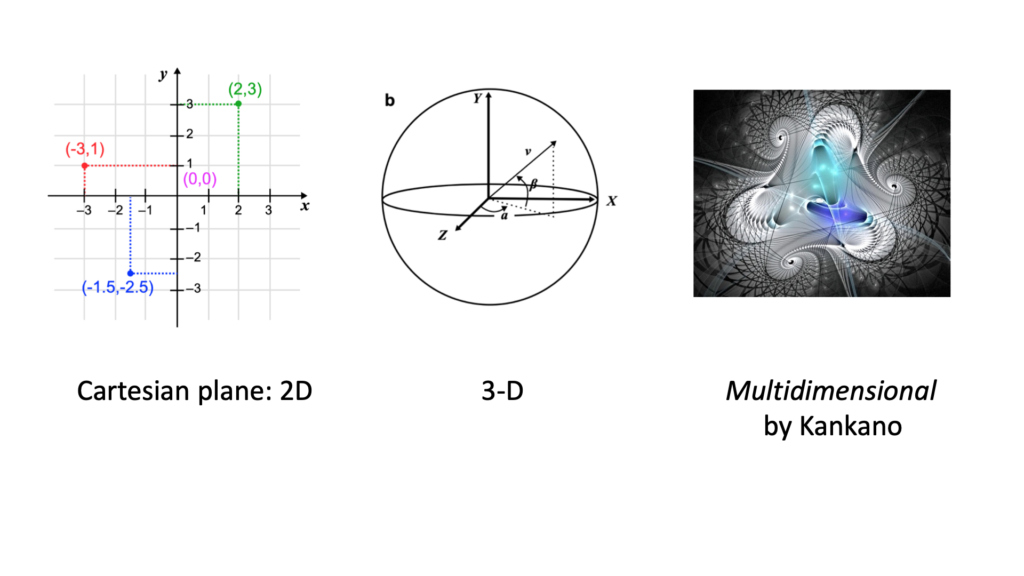

Clarity: A comprehensive way of viewing life, with a clearness of perception, thinking, and intentionality. This is seeing ourselves, the context of our life, our goals and intentions holistically. It is opening our mind to the Infinite and recognizing that like a wave on the ocean we express that ultimate Reality.

Situational Awareness: Right Mindfulness (from Buddha’s Eightfold Path). It means being aware of our thoughts, actions, and intentions in that moment with a gentle and caring attitude. Or as David Brooks has described it: a feel for the unique contours of the situation. An intuitive awareness of when to follow and when to break the rules. A feel for the flow of events, a special sensitivity, not necessarily conscious, for how fast to move and what decisions to take that will prevent a bad outcome. A sensitivity that flows from experience, historical knowledge, humility in the face of uncertainty, and having led a reflective and interesting life.

Joy: More than an emotion of delight, joy is a state of being and cherishing of the moment, feeling fulfilled, lacking nothing, and being content. A feeling that pervades your entire body, mind, and spirit.

Empathy, love, and compassion: This is our sense of responsibility for others. We feel what they feel and are moved to help relieve their suffering. These are the motivators and bonds that form a true intimacy with others.

Trust and lack of fear: As fears subside, the reality of something greater than ourselves increases and trust in its benevolence grows. It is a non-conceptual awareness that carries a sense of vitality, intelligence, and love.

Openness, curiosity and creativity: As fears subside, the innate nature of our original mind comes to the foreground: An inner and outer boundless field of awareness that is open, active, adaptable, dynamic, inquisitive, and creative.

Wisdom: The wisdom of our open and creative mind is available to respond intuitively, spontaneously, and appropriately in any circumstance that we encounter, without the need to conceptualize and rationalize. It transcends intellectual/conceptual knowing.