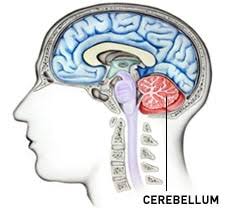

An often-overlooked human skill is our capacity to forecast future outcomes. We are excellent at anticipating an event in a variety of ways. Look-ahead functions or anticipatory mechanisms occur in how we read sentences and interpret speech. They also exist in how we carry out movements, like walking, grasping an object, or riding a bicycle. With reading or listening to a conversation, for example, we anticipate the words that come next. This facilitates the dynamics of a dialogue. Neuroscience studies show that the cerebellum executes some of these predictive operations for both motor and speech actions. This implies that how we control muscles to execute a movement is similar to how we manipulate sounds to construct a sentence.

An important aspect of our predictive brain is its ability to correct errors. Error correction is necessary to optimize and smooth out behavior by minimizing the adverse effects of deviations or unexpected perturbations in the system. It’s part of the flexibility, adaptability, and neuroplasticity that makes our brain unique. However, because we can expand the time window of processing, from the immediate present to extended past and future, it can complicate predictions. The predictive accuracy is inversely related to the timing of the event. During the very brief intervals required for movement or language, we do nicely. Otherwise, we are not very good. Yet we are predisposed to try. The result is stress, fear, depression and the myriad other disorders that arise when our predictions fail.

The solution to these prediction failures is easy to understand but hard to implement. It is to focus on what our brains evolved to do well. That is, to handle present-moment or immediate contingencies. Large portions of brain power are dedicated to this kind of creative, moment-by-moment living. The phone rings and I answer it; the water on the stove starts boiling over and I turn the gas off; I am watching television and getting angry at the story of the immigrant child who died while crossing the river with his dad. Most of this activity falls below our level of awareness. Error processing, on the other hand, triggers conscious processing and interruptions by our rational mind that require a look into the distant past or into the far future. This can cause problems if our ego decides to interfere. It is best, then, to let our predictive brain do the job of the moment and leave awareness to deal with the past and future. In other words, zip up that egoic intellect.

I will talk about the role of nonconscious and conscious processing in terms of present, past, and future thinking, as well as egoic thinking, in upcoming posts. Keep tuned!